Knowledge of cardiovascular risk patterns among professional athletes residing in rivers state, Nigeria

Abel Charles*

Department of Haematology and Blood Transfusion, Faculty of Basic Clinical Sciences, Gregory University, Uturu, Abia State, Nigeria.

*Corresponding author

Abel Charles, Department of Haematology and Blood Transfusion, Faculty of Basic Clinical Sciences, Gregory University, Uturu, Abia State, Nigeria.

DOI: 10.55920/JCRMHS.2023.04.001167

Abstract

Introduction: This study aimed to determine the knowledge of cardiovascular risks patterns among professional athletes residing in Rivers State.

Methodology: This descriptive, cross-sectional study had five objectives and research questions each and three research hypotheses and was conducted among professional athletes that train at four major stadia in Rivers State, with a sample size of 258 and analyzed with SPSS version 22.

Results: Among the respondents, 119(52.9%) knew of cardiovascular risk among athletes, with 204(79.4%) partaking in football and 88(34.6%) and 69(27.2%) been involved in sport for 6-10 years, 0-5 years respectively, while 130(50.8%) are not knowledgeable of risk factors of the heart and 90(50.3%) and 40(22.3%) know that added salt and smoking can put the heart at risk respectively, just as 141(64.1%) perceived football as the most commonly associated with cardiovascular risk and 54(24.5%) athletics. Also, heart failure, 141(66.5%) and hypertension 26(12.3%) were most common disorders, with 172(78.2%) experienced a disorder and 53(41.1%) and 24(18.6%) reporting it to doctors and trado-medical personnel respectively, while 113(61.7%) did not go for any medical treatment, and 7(49.0%) and 73(51.0%) managed and did not manage it properly respectively, while 151(73.3%) did not have cardiovascular symptom.

Conclusion: The study observed high level of knowledge of cardiovascular risks among professional athletes.

Keywords: Cardiovascular, risks, lifestyle, knowledge, heart failure, hypertension.

Introduction

An athlete is defined by the Webstar English dictionary, as an individual that participates in a sporting activity, such as running, swimming, walking, football, table tennis and any other recreational or competitive activity that involves physical exertion and energy expenditure. Athletic activities require physical, mental and emotional wellbeing for an optimal output. Thus, the cardiovascular system is important and its role is very critical to the athlete, as it contributes to the overall performance of the athlete. However, it suffices to observe that most professional athletes have little or no knowledge of their cardiovascular status and the risks of developing cardiovascular impairment. This may be due to inadequate enlightenment of the risk factors that may enthrone cardiovascular diseases.

The heart and cardiovascular system being vital components of the human body must function effectively for optimal daily activity, while for the athlete, it is important that the heart functions optimally, as any deviation from normalcy will impact negatively on the performance in sporting activities. Therefore, cardiac screening is important, to frequently monitor and ascertain the cardiac status of the individual. However, cardiac screening among athletes remains a huge and yet-to-be adequately resolved concern among cardiovascular experts and medical scientists (Schmehil et al., 2017).

Athletic activities have evolved into a source of employment and financial enrichment (Oladunni & Sanusi, 2013). Apart from these, a successful athletic career also confers celebrity status and global recognition on the athlete. This has largely endeared individuals to sports and other forms of athletic activities. Owing to the physical exertion involved in athletic activities, the body tends to cope with challenging requirements for cardiovascular homeostasis, thermoregulatory control and the upkeep of muscle energy (Oladunni & Sanusi, 2013). This is in addition to immunosuppression, occasioned by the exertion, which exposes athletes to opportunistic infections (Oladunni & Sanusi, 2013). By implication, any impairment or defect in any of the mechanisms will impact negatively on the athlete’s health and performance. The impairment in health is sometimes immediate, but may be the remote cause for future debilitative health conditions, such as cerebrovascular disease (CVD) and metabolic disorders such as diabetes mellitus.

There has been a steady rise in the incidence of athlete’s death globally, mainly associated with cardiovascular disorders (Maron et al., 2009). This has led to a reduced participation in active or competitive sports (Kovacs & Baggish, 2015; Schmehil et al., 2017). The first step, therefore, is for the athlete and managers of sporting activities to understand the important role of the cardiovascular system in the overall performance and general wellbeing of the athletes. This entails continuous screening of their cardiovascular function (Maron & Pelliccia, 2016). However, there has been reported difference in cardiac function and structure among people of different race, including athletes (Uberoi et al., 2011).

In some countries like Turkey, Brazil and Uruguay, cardiovascular diseases have been observed to be the leading cause of morbidity and mortality (Andsoy et al., 2015), accounting for approximately 295,457 (47.73%) deaths in the country (T. C. Ministry of Health, 2010). Globally, an estimated 44 million youths participate in sporting activities each year, about 10 million at the high school level and approximately half a million at the college level (Kovacs & Baggish, 2015). Majority of these athletes lack knowledge of their cardiovascular status. Kovacs and Baggish (2015) posit that some of them may even have a pre‐existing heart disease, such as congenital heart disease, before indulging in the strenuous sporting schedules. The global prevalence of sudden cardiac death among athletes is estimated at 0.61 in 100,000 (Maron et al., 2009). The rarity of its occurrence does not suffice the fact that if appropriate measures are not taken to monitor cardiac function and status among this group of individuals (athletes), the occurrence of deaths attributable to cardiovascular dysfunction is not significant. However, this can be completely prevented or reduced, if proper modalities are put in place to monitor and diagnose its existence among athletes.

The risk factors for cardiovascular diseases are broadly grouped into modifiable and non-modifiable. Modifiable factors can be altered with a change in lifestyle, but not non-modifiable risk factors, which are mostly natural in development. Modifiable risk factors include: dyslipidemia, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, overweight, obesity, smoking, drugs and chemical substances, physical inactivity (sedentary lifestyle) and unhealthy diet, while the non-modifiable are age, sex and family history (D’Agostino et al., 2008; Yusuf et al., 2004). Some kinds of sport also serve factors for developing cardiovascular diseases, as reported for the American National Football League, where they are 52% more likely to gain weight and developing coronary heart disease mortality (Matthew & Wagner, 2008), thus, formulation of sport nutrition guidelines, to optimize the health and performance of athletes (Ray & Fowler, 2004; Rodriguez et al., 2009).

There has also been dispute on the authenticity that regular and rigorous exercise improves health. While some authors posit that it is of benefit to the human body, others argue otherwise, with a study from the Copenhagen Heart Study reporting that vigorous jogging presents similar heart rates as those without any form of exercise, hazard ratio, 1.97; 95% CI, 0.48-8.14; and hazard ratio, 0.66; 95% CI, 0.32-1.38, respectively (Schnohr et al., 2015). Another study also reported that about 20% of athletes who undertake endurance sports, such as marathon, have an increased left atrium, hypertrophy (Maron & Pelliccia, 2006). Maron and Pelliccia (2006) also reported abnormal patterns of echocardiography and other cardiovascular findings in about 40% of trained athletes, in addition to transient arrhythmias and cardiac conduction alteration.

Some athletes indulge in the use of drugs to boost their performance during training and competitive activities (Holmes et al., 2013). The role of drugs and other chemicals in the etiology of cardiovascular diseases cannot be underestimated, but they alter vascular and other systems functions. The negative effects of drugs and abuse of substance among professional athletes is in the public glare, with notable retired athletes coming down with severe neuromuscular complications and defects as their age advances. Among the commonly used and often abused drugs among professional athletes are steroids and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) (Matz, 2011).

This aspect of sports is broadly lacking in most climes, mainly due to constraints of finance, facilities and other factors. At the moment, there is no standard for the screening of athletes and possible evaluation of cardiovascular abnormalities among them, which is a huge concern to clinicians and athletes (Schmehil et al., 2017). In a study on the sensitivity and specificity of cardiovascular screening results, about 68% of the respondents were observed to have an existing cardiac abnormality; a further review observed that about half were false positive results, while another 31% went for further screening and were observed to not have any form of heart-related abnormality (Harmon et al, 2015). Although cardiovascular disease among athletes resulting in unanticipated death is rare, it occurs. A study in the United States of America on the causes of sudden death among athletes, using its registry from 1980-2011, revealed that among 6,082 deaths, 842 were of cardiovascular origins with a male to female ratio of 6.5:1, with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy being the most common cause at 36%, while other cardiac causes were congenital coronary artery anomalies, arrythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy and long QT syndrome (Maron et al., 2016). This is the situation in the region of this study, in addition to poor documentation, and this study intends to fill this gap.

The Health Belief Model was used for this study. The model explains the process of change in relation to health behaviour and is frequently used in health education, health promotion and disease prevention studies (Polit, 2004). Although the model was originally developed in 1850, it was expanded by Levential et al. (1928). The model breaks down health decisions into stages, providing catalogue of variables that influence health decisions and actions or inactions. However, it does not provide a pattern of exactly how these operate, but the likelihood that if an individual follows a preventive behaviour, it is likely influenced by subjective weighing of the costs and benefits of such actions. It is accompanied by some assumptions;

- An individual will take a health-related action if the person feels that a negative health condition can be avoided.

- An individual will take preventive action, having in mind that by taking a recommended action, the negative health conditions will be avoided, therefore, the person needs to see the benefits. If the benefits are not seen, it will be difficult to take action or maintain it.

- The individual must feel confident that keeping to the recommended action, he or she has the necessary knowledge and skills in a supportive environment to carry out the required actions.

According to Onega (2000), the model comprises of three components; Individual perception- these are directly related to the person involved, the athlete, in this respect, Perceived susceptibility- it brings to bare certain health conditions/problems that the athletes must evaluate before embarking on an exercise, dietary or lifestyle regimen and Perceived seriousness: the notion about severity of the medical condition.

METHODOLOGY

This descriptive, cross-sectional study, using a proportionate sampling technique, was conducted in five stadia in Rivers State. These are the Sharks Football Club stadium, the University of Port Harcourt stadium, Go Round Football Club stadium, Adokiye Amiesimaka stadium and the Liberation stadium. These selections are premised on the fact that these are the stadia where active sporting activities take place within the state and are located in different local government areas of the state and of international standards, thus, giving equal opportunity for cultural diversity. Rivers State is one of the 36 states in Nigeria, with Port Harcourt as the capital and English language is the central and official language The participants were professional athletes resident in the state, train at any of the centers considered and aged 15-45 years. A sample size of 258 was obtained, using the prevalence of 40% from a previous study by Marion and Pellicida (2006).

A semi-structure questionnaire was presented to the study supervisor for validation, before commencement, while Ethical approval was obtained from the Institute of Sports Medicine, University of Port Harcourt and Consent obtained from each participant. The data was analyzed using statistical package for social sciences version 21 and presented in tables as frequencies and percent.

Results

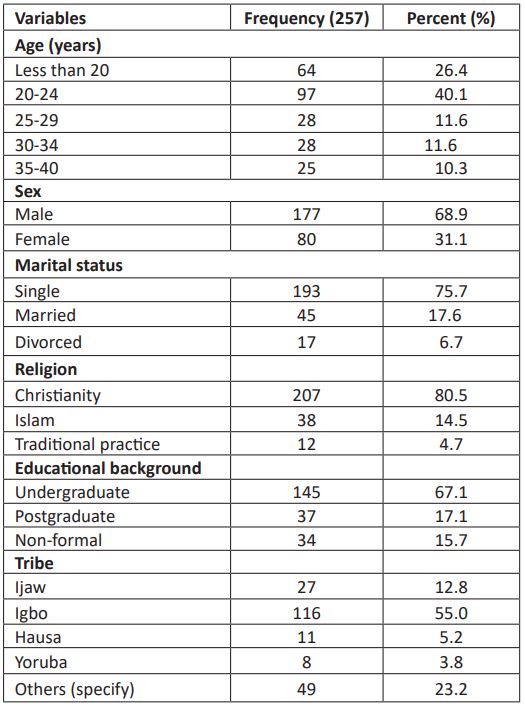

Table 1: Socio-demographic characteristics of the respondents

The age distribution of the respondents show that 97(40.1%) were between 20-24 years, being the most, followed by those less than 20 years old, 64(26.4%), while the least were between 35-40 years old, 25(10.3%). The gender feature show males were more, 177 (68.9%), and 193(75.7%), 45(17.8%) and 17(6.7%) were single, married and divorced respectively. regarding the religious inclination, majority were Christians, 207(80.5%) and the least are of traditional practice, 12(4.7%), while 145(67.1%) were undergraduates, 37(17.1%) were post-graduates and 34(15.7%) had non-formal education, just as 116(55.0%) are of Igbo extraction, followed by 49(23.2%) are of tribes other than those listed and the least were of Yoruba extraction, 8(3.8%).

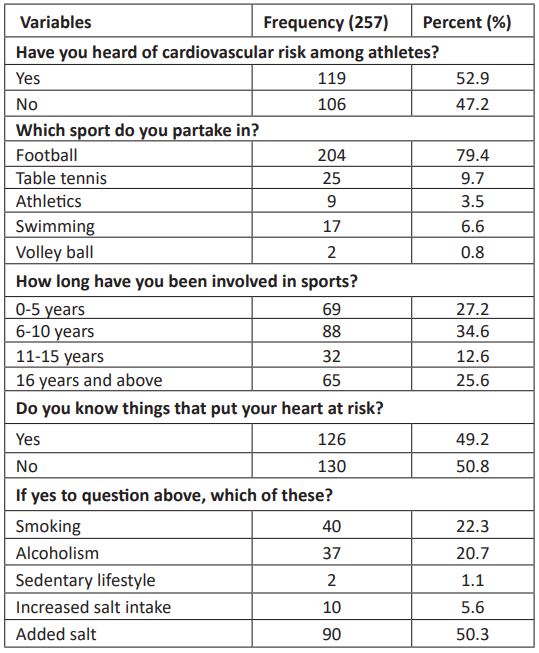

Table 2a: Knowledge of cardiovascular risk among the respondents.

Table 2 above shows the results of cardiovascular risk among the respondents. It shows that 119(52.9%) have heard of cardiovascular risk among athletes, but 106(47.2%) have not. 204(79.4%) partake in football, 25(9.7%) and 17(6.6%) are involved in table tennis and swimming respectively, while the least, 2(0.8%) partake in volley ball. This study observed that 88(34.6%), 69(27.2%) and 65(25.6%) respondents had been involved in sport for 6-10 years, 0-5 years and 16 years and above respectively, while 130(50.8%) and 126(49.2%) are not knowledgeable of things that can put their heart at risk and know about it respectively. Similarly, 90(50.3%), 40(22.3%) and 37(20.7%) posited that added salt, smoking and alcoholism can put the heart at risk respectively.

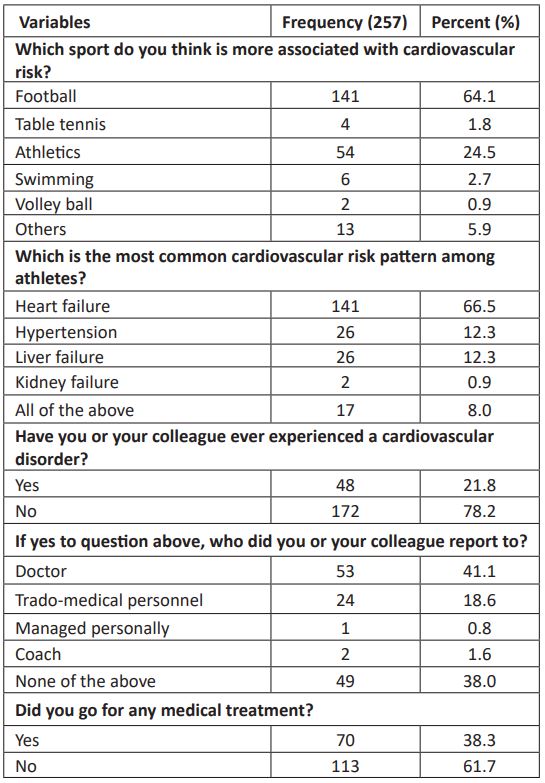

Table 2b: Knowledge of cardiovascular risk among the respondents

In table 2b above, 141(64.1%) view football as the sport most associated with cardiovascular risk, 54(24.5%) mentioned athletics and 2(0.9%) mentioned volley ball, being the least. The most common cardiovascular risk is heart failure, 141(66.5%), followed by 26(12.3%) each for hypertension and liver failure and 2(0.9%) for kidney failure. 172(78.2%) respondents and their colleagues have not experienced cardiovascular disorder, with 53(41.1%) and 24(18.6%) reporting to doctors and trado-medical personnel respectively, while 113(61.7%) did not go for any medical treatment and 70(38.3%) did.

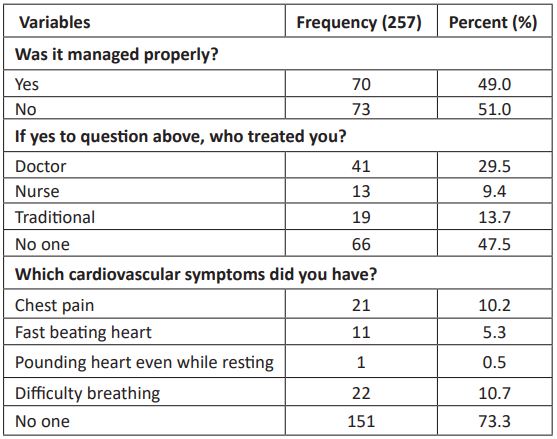

Table 2c: Knowledge of cardiovascular risk among the respondents

In table 4.2c above, 73(51.0%) and 70(49.0%) did not manage the cardiovascular disorder properly and managed it properly respectively. Majority of the respondents, 151(73.3%) did not have a cardiovascular symptom, but 22(10.7%), 21(10.2%) and 11(5.3%) experienced difficulty breathing, chest pain and fast beating heart respectively.

Discussions

This study shows reported that 119(52.9%) have heard of cardiovascular risk among athletes, but 106(47.2%) have not. This finding is in contrast with the findings of Schmehil et al. (2017) and Drezner et al. (2013) which reported poor knowledge of cardiovascular risk and its development in their distinct studies. The variation in the two studies as against this present study may be due to environmental variations in the studies, as developing countries are reported to have poor knowledge of most common features of their life. 204(79.4%) partake in football, 25(9.7%) and 17(6.6%) are involved in table tennis and swimming respectively. this finding agrees with that of Uberoi et al. (2011), who reported in their study that, not only does football have the highest number of athletic participation, it also has the highest number of followership (fan base) globally. This study observed that 88(34.6%), 69(27.2%) and 65(25.6%) respondents had been involved in sport for 6-10 years, 0-5 years and 16 years and above respectively. This finding has the tendency to vary, depending on the setting of the study and individual responses from participants. Also, 130(50.8%) and 126(49.2%) are not knowledgeable of things that can put their heart at risk and know about it respectively. The poor level of knowledge of cardiovascular risks observed in this study is in tandem with the findings of Drezner et al. (2013) Similarly, 90(50.3%), 40(22.3%) and 37(20.7%) posited that added salt, smoking and alcoholism can put the heart at risk respectively and is in agreement with the findings of Drezner et al. (2013) as well. This study further observed that, 141(64.1%) respondents viewed football as the sport most associated with cardiovascular risk and 54(24.5%) mentioned athletics. Commonly, one would envisage that the sport with the highest number of participation and followership should be associated with more risks. This can be considered in the concept that more involvement entails more experience and contact sport, according to Schmehil et al. (2017) is more associated with incidences of intense work and physical activity, thus, more generalized risk to several organs of the body. The most common cardiovascular risk is heart failure, 141(66.5%), followed by 26(12.3%) each for hypertension. Disorders directly relating the heart are usually associated with physical activities that are strenuous in nature. To this end, the finding in this study, agree with the finding of Uberoi et al. (2011) which also noted that heart failure and hypertension were the most common disorders associated with athletic and sport activities. The finding also is in tandem with those of Weiner et al. (2013) and Whelton et al. (2007) regarding hypertension among professional athletes. It is worthy, however, to note that, sedentary and other non-physical activities come with their respective attendant disadvantage to the heart and its function. 172(78.2%) respondents and their colleagues have not experienced cardiovascular disorder, with 53(41.1%) and 24(18.6%) reporting to doctors and trado-medical personnel respectively, while 113(61.7%) did not go for any medical treatment. This finding is consistent with developing countries and is in the context with report by the CDC (2004) concerning the report of medical conditions and seeking professional management of such conditions. Also, this study observed that 73(51.0%) and 70(49.0%) did not manage the cardiovascular disorder properly and managed it properly respectively, while majority of the respondents, 151(73.3%) did not have a cardiovascular symptom. The observation of symptoms relating to an ailment varies among individuals, while in others, it may remain insidious until it reaches an advanced stage. This finding is in agreement with the findings by Tucker et al. (2009), Ray and Fowler (2004), Rodrigues et al. (2009) and Seldon et al. (2009).

Summary of findings

The study observed that 119(52.9%) respondents knew of cardiovascular risk among athletes, but 106(47.2%) do not, with 204(79.4%) partaking in football, while 25(9.7%) and 17(6.6%) partook in table tennis and swimming respectively. Also, 88(34.6%), 69(27.2%) and 65(25.6%) respondents had been involved in sport for 6-10 years, 0-5 years and 16 years and above respectively, while 130(50.8%) and 126(49.2%) are not knowledgeable of things that pose risk to their heart and know about it respectively and 90(50.3%), 40(22.3%) and 37(20.7%) know that added salt, smoking and alcohol can put the heart at risk respectively, just as 141(64.1%) perceived football as the sport most commonly associated with cardiovascular risk and 54(24.5%) mentioned athletics. Also, heart failure, 141(66.5%) and hypertension 26(12.3%) were the most common disorders, with 172(78.2%) experiencing a disorder, and 53(41.1%) and 24(18.6%) reporting it to doctors and trado-medical personnel respectively, while 113(61.7%) did not go for any medical treatment, just as 73(51.0%) and 70(49.0%) did not manage the disorder properly and managed it properly respectively, while 151(73.3%) did not have a cardiovascular symptom.

Conclusions

The study observed high level of knowledge of cardiovascular risks factors among professional athletes, with about half of them experiencing it and reporting same to doctors and coaches, as well as, managing the cardiovascular disorders through trado-medical medicine practitioners mostly and at other times by medical practitioners. It is pertinent that more enlightenment is carried out, while appropriate management modalities are enshrined, as this will enhance their professional performance and longevity in their chosen profession.

Recommendation

More enlightenment should be carried out by the appropriate authourities concerning the risk factors of cardiovascular disorders and how it can be managed.

References

- Andsoy, I. I., Tastan, S., Iyigun, E., & Kopp, L. R. (2015). Knowledge and Attitudes towards Cardiovascular Disease in a Population of North Western Turkey: A Cross- Sectional Survey. International Journal of Caring Sciences, 8(1), 145-152.

- D’Agostino, R. B., Vasan, R. S., & Pencina, M. J. (2008). General cardiovascular risk profile for use in primary care: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation, 117(6), 743-753.

- Drezner, J. A., Ackerman, M. J., & Anderson, J. (2013). Electrocardiographic interpretation in athletes: the ‘Seattle criteria’. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 47:122-124.

- Harmon, K. G., Zigman, M., & Drezner, J. A. (2015). The effectiveness of screening history, physical exam, and electrocardiogram to detect potentially lethal cardiac disorders in athletes: a systematic review/meta-analysis. Journal of Electrocardiology, 48: 329-338.

- Holmes, N., Cronholm, P. F., Duffy, A. J., & Webner, D. (2013). Non-steroidal anti- inflammatory drug use in collegiate football players. Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine, 23: 283–286.

- Kovacs, R., & Baggish, A. L. (2015). Cardiovascular adaptation in athletes. Trends in Cardiovascular Medicine, 26(1), 46-52.

- Maron, B. J., Doerer, J. J., & Haas, T. S. (2009). Sudden deaths in young competitive athletes: analysis of 1866 deaths in the United States, 1980-2006. Circulation, 119: 1085-1092.

- Maron, B. J., Haas, T. S., & Ahluwalia, A. (2016). Demographics and Epidemiology of Sudden Deaths in Young Competitive Athletes: From the United States National Registry. American Journal of Medicine, 129: 1170-1177.

- Maron, B. J., Shirani, J., & Poliac, L. C. (1996). Sudden death in young competitive athletes. Clinical, demographic, and pathological profiles. Journal of American Medical Association, 276: 199-204.

- Matthew, M., & Wagner, D. R. (2008). Prevalence of overweight and obesity in collegiate American football players, by position. Journal of the American College of Health, 57(1), 33-38.

- Oladunni, M. O., & Sanusi, R. A. (2013). Nutritional Status and Dietary Pattern of Male Athletes in Ibadan, South Western Nigeria. Nigeria Journal of Physiologic Science. 28: 165-171.

- Ray, T. R., & Fowler, R. (2004). Current issues in sports nutrition in athletes. South Medical Journal, 97(9), 863-866.

- Rodriguez, N. R., DiMarco, N. M., & Langley, S. (2009). Position of the American Dietetic Association, Dietitians of Canada, and the American College of Sports Medicine. Journal of the American Dietetics Association, 109(3), 509-527.

- Schmehil, C., Malhotra, D., & Patel, D. R. (2017).Cardiac screening to prevent sudden death in young athletes. Translational Paediatrics, 6(3), 199-206.

- Selden, M. A., Helzber, J. H., & Waeckerle, F. (2009). Early cardiovascular mortality in professional football player: fact or fiction? American Journal of Medicine, 122(9), 811- 814.

- C. Ministry of Health. (2010). General Directorate of Primary Health Care, Cardiovascular Diseases of Turkey Prevention and control programs; Primary, Secondary and strategic plans and action plans for tertiary prevention (2010-2014). pp 9. Ankara.

- Tucker, A. M., Vogel, R. A., Lincoln, A. E., Dunn, R. E., Ahrensfield, D. C., Allen, T. W., Castle, L. W., Heyer, R. A., Pellman, E. J., Strollo, P. J., Wilson, P. W., & Yates, A. P. (2009). Prevalence of cardiovascular disease risk factors among National Football League players. Journal of American Medical Association, 301(20), 2111–2119.

- Uberoi, A., Stein, R., & Perez, M. V. (2011). Interpretation of the electrocardiogram of young athletes. Circulation, 124: 746-757.

- Whelton, P. K., Carey, R. M., Aronow, W. S., Casey, D. E., Collins, K. J., Dennison, K., Himmelfarb, C., DePalma, S. M., Gidding, S., Jamerson, K. A., Jones, D. W., MacLaughlin, E. J., Muntner, P., Ovbiagele, B., Smith, S. C., Spencer, C. C., Stafford, R. S., Taler, S. J.,Thomas, R. J., Williams, K. A., Williamson, J. D., & Wright, J. T. (2017). ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Journal of The American College of Cardiologists, 6, 2020.

- Yusuf, S., Hawken, S., & Ounpuu, S. (2004). Effect of potentially modifiable risk factors associated with myocardial infarction in 52 countries (the INTERHEART study): case- control study. Lancet, 364(9438), 937-952.